Civil War

Where History Shaped the Shenandoah Valley

-

It was cold on Sunday, March 23, 1862. It had snowed a few days before and the farmland was still covered with soft white crystals. But the sunshine that day had left pockets of cold slush in the fields. Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson with his small Confederate army of less than 3,000 soldiers advanced to Kernstown following a 35-mile march from the Mount Jackson area. His commander’s guidance was clear – try to keep the Union Army in the Valley but avoid a decisive engagement.

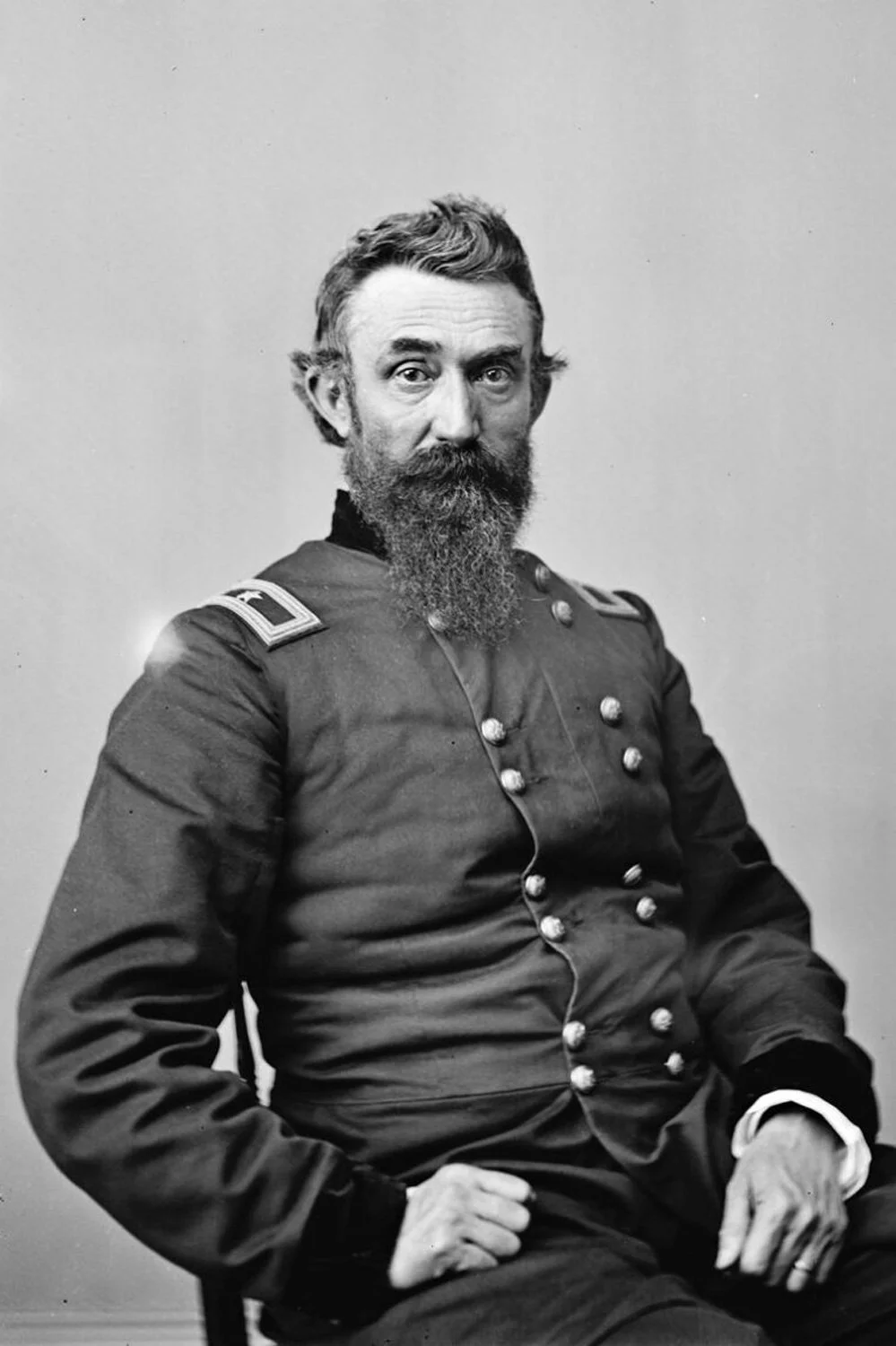

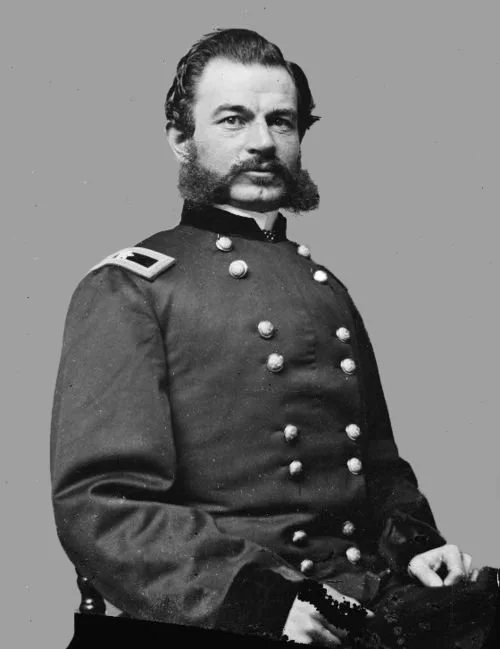

Acting on faulty intelligence which led him to believe that much of the Northern Army had moved east out of the Valley, Jackson sensed an opportunity to retake Winchester and ordered an advance. Here at the Pritchard Farm in Kernstown, Jackson's small division met a much larger Union division of 7-8,000 soldiers commanded by Col. Nathan Kimball whose superior, Gen. James Shields, had been wounded the day before and was recovering in Winchester.

The battle opened with Union forces strategically straddling the Valley Pike (U.S. Route 11) and their 16 artillery pieces arrayed on the commanding heights of Pritchard's Hill. Jackson ordered Col. Fulkerson and Gen. Garnett to mount an attack on the hill to force the cannoneers to retire. After taking heavy losses from the relentless artillery fire while advancing northward across the Pritchard Farm's marshy open fields, this attacking Confederate force quickly moved westward to the relative safety of the woods on Sandy Ridge about a half mile away. Here they were joined by other infantry and artillery units of Jackson's command moving up from the south.

Seeing this, Kimball ordered his infantry to Sandy Ridge. After winning a foot race for the protection of the stone walls lining the rolling hills, the Confederate infantry poured devastating fire into the approaching Union units. Late in the afternoon, however, overwhelming Union numbers took their toll and the Southern soldiers began to run out of ammunition. As the day ended, the Confederates were forced to retreat leaving the Pritchard Farm and Sandy Ridge in Northern hands.

"I do not recollect of ever having heard such a roar of musketry", wrote Jackson after the battle. When darkness ended the battle, casualties on both sides totaled over 1,000 men. Kernstown was the first major battle fought in the Valley, and although it represented an inauspicious start, it launched Jackson's famous Valley Campaign of 1862. Union leaders, convinced their opponent had a much larger army, cancelled plans to move most of their army out of the Valley, depriving Union Gen. George McClellan of reinforcements for his planned advance on Richmond. This turned a rare Jackson defeat into what many historians consider a strategic victory for the Confederate Army.

-

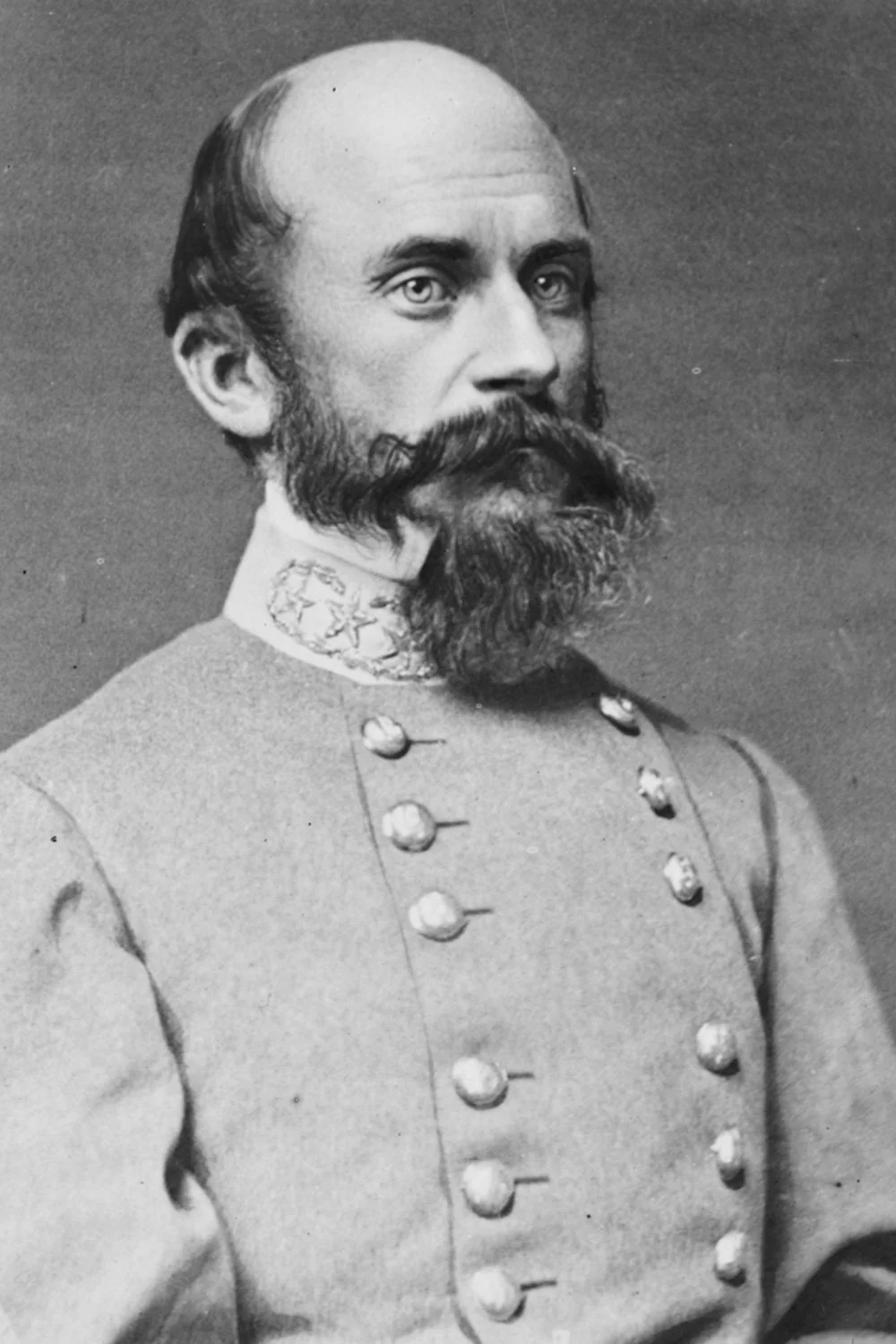

In June 1863, Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia headed for the Gettysburg Campaign. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Second Corps led the way, attacking the outnumbered Union troops of Gen. Robert Milroy defending the town of Winchester. Milroy, advised by Union leadership to not to try to defend the town, ignored command guidance to the peril of himself (he was a “wanted” man by the Confederates and barely escaped capture) and of his command. After some sharp Cavalry skirmishes south of Newtown, VA on June 12th, Ewell continued northward leading to engagements on the 13th on what today is the Kernstown Battlefield.

After being pushed back initially by the 110th OH and the Union guns on Pritchard’s Hill, the Maryland (Confederate) troops attacked from the Union front with the support of the 9th Louisiana troops who were attacking the Union defenders from the west. This combined force pushed the green, but stubborn, Union troops off of Pritchard’s Hill sending them north towards town. Nearly simultaneous to the Confederate advance on Pritchard’s Hill, four of Gen. John Gordon’s six veteran Georgia regiments attacked the very inexperienced 12th West Virginia Infantry on Sandy Ridge, quickly driving them back toward town.

The Union losses in this short fight were considerable with the 123rd Ohio reporting 75 casualties alone. Confederate casualties are unknown but were probably a good bit lower than Union casualties. After the initial engagements on Sandy Ridge and around Pritchard’s Hill, Ewell’s forces continued their assault on June 14th into Winchester proper that culminated with the near annihilation of Milroy’s force on the morning of June 15th near Stephenson’s Depot, a few miles north of town. The outcome of this battle opened a clear path for the Confederate invasion through Maryland into Pennsylvania, culminating in what is regarded by many historians as the most decisive battle and turning point of the Civil War, the battle of Gettysburg.

-

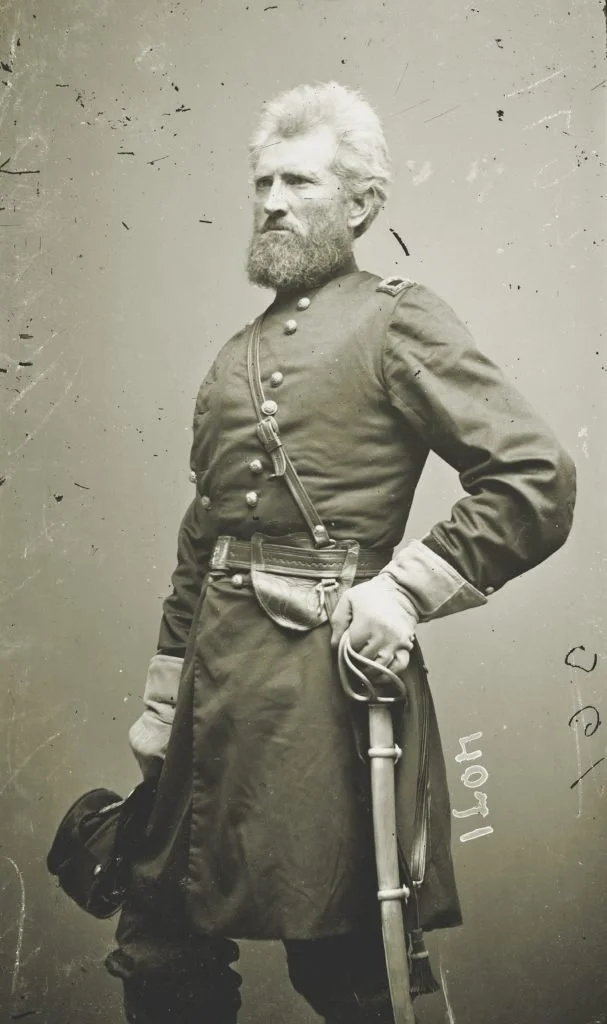

Following his raid to the outskirts of Washington, D.C. in mid-July 1864, Confederate Gen. Jubal Early withdrew his force to the lower Shenandoah Valley. Believing that Early had withdrawn to Petersburg, VA, Union Gen. Horatio Wright ordered the VI and XIX Corps from the Valley to the Petersburg/Richmond area to reinforce Gen. Ulysses Grant, leaving Gen. George Crook in Winchester with less than 12,000 soldiers to guard the Valley.

Having learned of the diminished Union presence in the Valley, Early pushed north from Strasburg toward Winchester on July 24, 1864 with nearly 17,000 troops. He intended to drive Gen. Crook's force out of the city and the Valley. Crook, believing that only a small cavalry force faced him, ordered his units to push south from Winchester and scatter the Confederates.

Once again, Union artillery graced the heights of Pritchard's Hill to support the Union advance. Crook's regiments made it as far as the Opequon Church just south of Pritchard's farm in Kernstown before being forced back by Gen. Early's amassed force. As they pulled back, fierce fighting tore at the Union ranks lined up behind the stone wall along the entrance lane to the Pritchard farm. Union Col. James Mulligan tried to rally his troops behind the wall, but they were heavily outflanked by Confederate troops advancing from three directions.

During his stand behind the stone wall, Col. Mulligan was badly wounded by Confederate sharpshooters. As his troops were being fired upon while attempting to carry him from the field, he ordered them to "Lay me down and save the flag." Thus began the retreat of the Union force north into Maryland. Mulligan was carried into the Pritchard house and cared for by the Pritchards, but his severe wounds caused his death two days later.

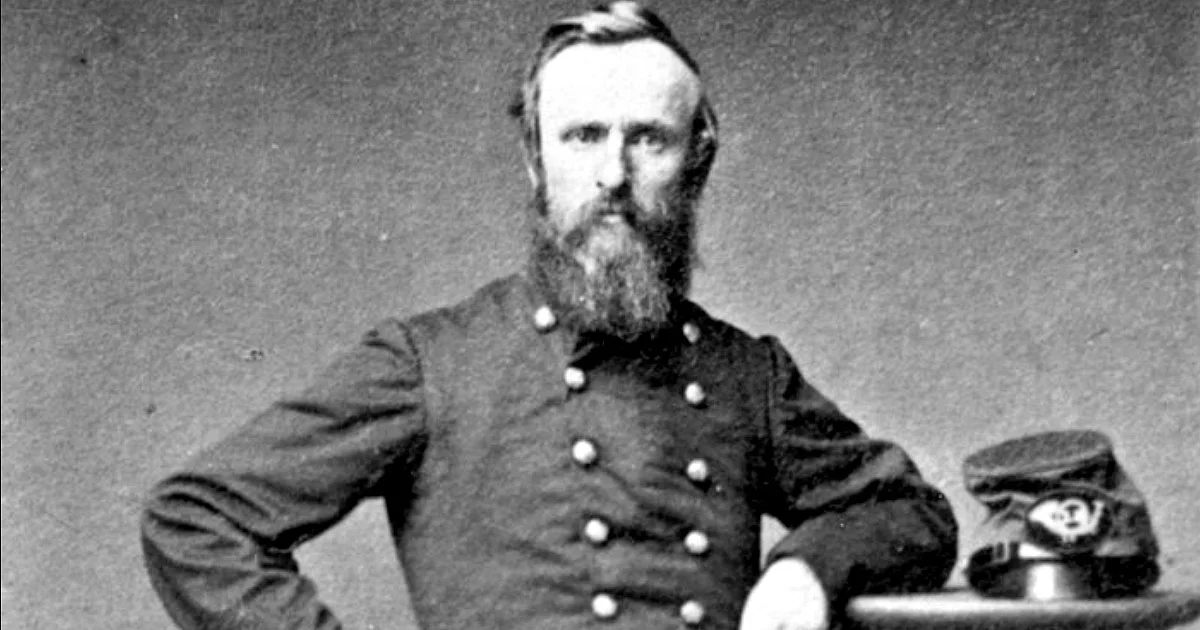

The decisive Confederate victory at the Second Battle of Kernstown was to be their last in the Valley and opened the way for Early's cavalry to ride into Pennsylvania and burn Chambersburg. Union leadership, reacting to these Confederate actions, greatly reinforced their army in the Valley and placed it under the command of Gen. Philip Sheridan. The Union victories at Third Winchester, Fisher’s Hill and Cedar Creek, along with the Great Burning of the Shenandoah Valley were to follow. Stonewall Jackson’s prediction that, "If this Valley is lost, Virginia is lost" finally came true, when six months after Early's defeat at Cedar Creek, Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Gen. Grant at Appomattox Court House.

-

In November 1864, the Union Army of the Shenandoah commanded by Gen. Philip Sheridan established a large complex of winter camps on grounds that were adjacent to the Opequon Creek, just west of Newtown (now Stephens City) and south of Winchester, Virginia. Named for Gen. David Russell who was killed at the Battle of Third Winchester in September 1864, Camp Russell was the largest of the winter camps in the Valley during the war. It grew to be a two-mile-long complex consisting of separate encampments for each of the Army of the Shenandoah’s individual regiments, as well as a hospital system, and was protected by a four-mile-long system of earthworks and trenches that were installed on both sides of the Valley Pike (south of what, today, is the intersection of Interstate 81 and Virginia Route 37).

The western/right flank of Camp Russell, which encompassed the Kernstown Battlefield property, was manned by the cavalry corps led by Gen. Alfred Torbert. Torbert established his headquarters in Samuel Reese Pritchard’s house, with his division commanders, Gens. Wesley Merritt, William Powell, and George Armstrong Custer, headquartered nearby in similarly-sized homes.

While Camp Russell was in place for less than two months, it was a time of great loss for the Pritchard family. Reportedly, Mr. Pritchard confronted Gen. Torbert about Union soldiers violating orders protecting his property and was told in simple terms, “We must have it.” The Pritchards’ losses during this time included 23,000 fence rails, 900 feet of stone fencing, a portable steam engine (later recovered, but damaged) and a large quantity of cut lumber. After the war, the Pritchards filed a claim against the federal government for these losses, but their claim was denied as Mr. Pritchard was unable to definitively prove that he was a Union supporter, a perquisite to any federal compensation.

Did You Know?